Key Findings

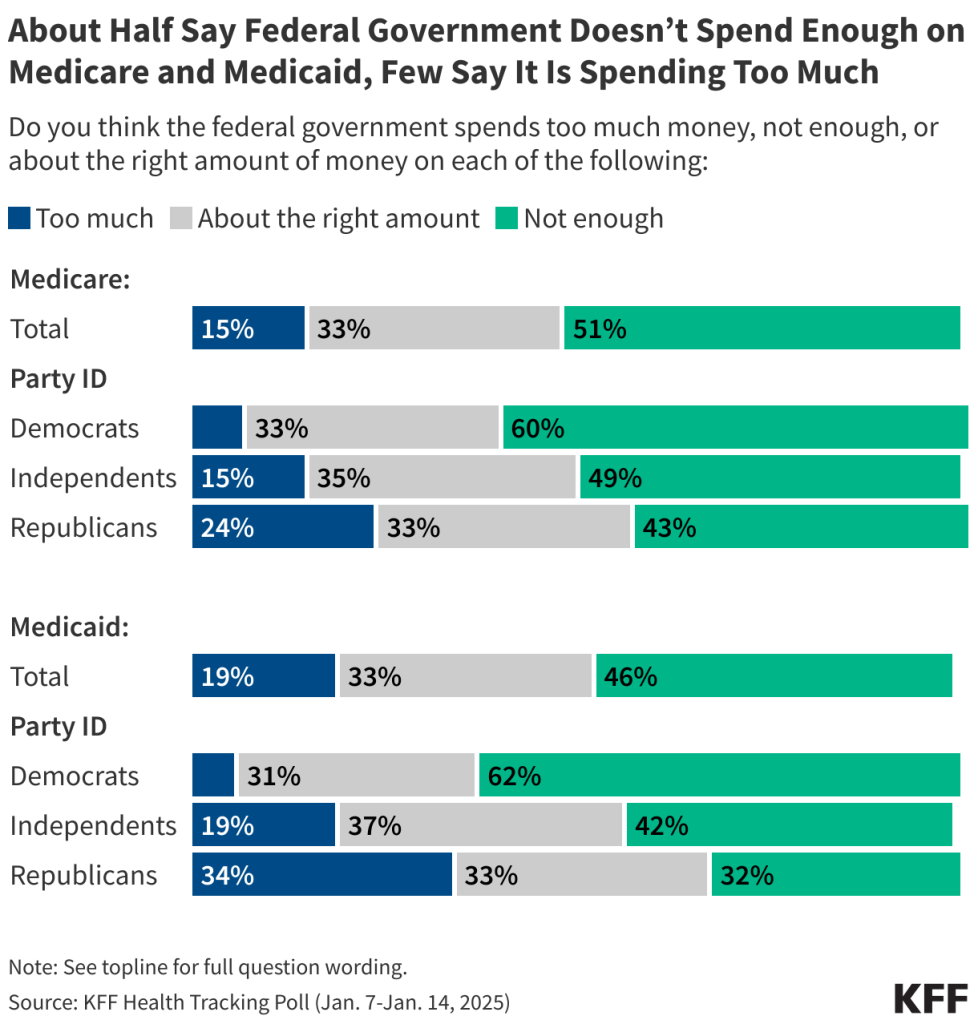

- Both Medicare and Medicaid continue to be viewed favorably by large majorities of the public, including majorities of Republicans, Democrats, and independents. While lawmakers are discussing changes to Medicaid and Medicare including possible spending cuts, about half of the public think the federal government isn’t spending enough on each of these programs. Half (51%) say the federal government spends “not enough” on Medicare, and nearly half (46%) say the same about the Medicaid program. Across both programs, the share of the public who say the government isn’t spending enough is more than twice the share who say the government is spending “too much.”

- The latest KFF Health Tracking Poll also shows bipartisan consensus for some health policy priorities for the new presidential administration and Congress, especially around oversight and regulation. Majorities of the public – including about half or more across partisans – say boosting health care price transparency rules (61%), setting stricter limits on chemicals found in food supply (58%), and more closely regulating the process used by health insurance companies when they approve or deny services or prescription drugs (55%) should be a “top priority” for the incoming administration and Congress. Expanding the number of prescription drugs that the federal government negotiates the Medicare price on is also ranked as a “top priority” by a majority of the public including two-thirds of Democrats, 54% of independents, 48% of Republicans and three-fourths of people who are currently enrolled in Medicare.

- While the public is largely in-line with some of the administration’s potential health care priorities, other possible policy actions are seen as lower priorities, and in some cases, larger shares of the public say they “should not be done.” The public is divided on whether the administration should prioritize recommending against fluoride in local water supplies, with the same share saying it should be a “top priority” (23%) as say it “should not be done” (23%). In addition, less than one in eight adults (including fewer than a quarter of Republicans) say reducing federal funding to schools that require vaccinations (15%), limiting abortion access (14%), or reducing federal spending on Medicaid (13%) should be a “top priority,” while at least four in ten say each of these “should not be done.”

- Nearly two-thirds of adults (64%) hold a favorable view of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), but views on the future of the law are still largely partisan. Four in ten Republicans (40%) say repealing the legislation should be a top priority, while half of Democrats (50%) say extending the enhanced subsidies for people who buy their own coverage should be a top priority. Overall, most of the public is worried about the level of benefits for people who buy their own coverage through the ACA marketplaces including nearly nine in ten Democrats (86%), nearly eight in ten independents (78%), and nearly half of Republicans (47%).

- Overall, about three-fourths (73%) of the public thinks that reducing fraud and waste in government health programs could lead to reductions in overall federal spending – which is the goal of Trump’s newly formed government efficiency program, but many also think it will result in a reduction of benefits. More than half of the public say reducing fraud and waste could lead to reductions in the benefits people receive from the Medicaid and Medicare programs.

Public’s Health Care Priorities

As President-elect Trump takes office on January 20th with Republican majorities in both chambers of Congress, the public is sending mixed messages on how they prioritize key components of the Trump administration’s health agenda. While Americans across partisanship largely embrace prioritizing increased regulation and oversight such as boosting price transparency rules and setting stricter limits on chemicals in the food supply, there are other aspects of the Republican agenda the public does not support – most notably, reducing federal funding to Medicaid.

When asked about a variety of health care proposals, including those put forth by Republican and Democratic lawmakers, about six in ten say boosting price transparency rules to ensure health care prices are available to patients (61%) should be a “top priority,” and a similar share say the same about setting stricter limits on chemicals found in the food supply (58%). A majority (55%) also say more closely regulating the process used by health insurance companies when they approve or deny services or prescription drugs is a top priority. Overall, while health care ranks lower than other policy areas such as immigration, foreign policy, and the economy; majorities of the public – including half or more across partisanship – say each of these should be a “top priority” for Congress and the new Trump administration.

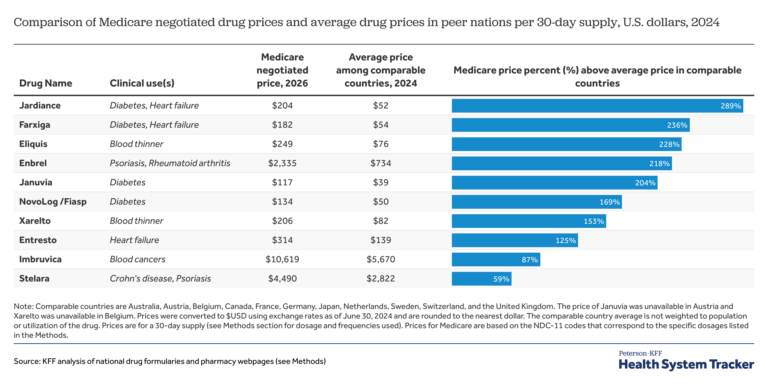

When it comes to proposed changes to two key health care legislations: the Inflation Reduction Act’s provisions to allow the federal government to negotiate the Medicare price of prescription drugs as well as the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), larger shares of the public support actions to expand or strengthen these laws rather than repealing them. More than half of the public (55%) say expanding the number of prescription drugs subject to Medicare price negotiation should be a top priority, twice the share who prioritize rolling back this provision (28%). On the ACA, about a third (32%) prioritize extending the enhanced subsidies for people who buy their own health coverage while a quarter of the public (27%) say repealing and replacing the ACA is a top priority.

Other health care issues, many of which may be the focus of the Trump administration, are seen as even lower priorities for the incoming administration with substantial shares of the public saying they “should not be done.” Less than a quarter of the public think changing recommendations for fluoride in local water supplies (23%) should be a “top priority,” which is identical to the share who say it should not be done. Less than one in eight say reducing federal funding to schools that require vaccinations (15%), limiting abortion access (14%), and reducing federal funding on Medicaid (13%) should be top priorities. At least four in ten of the public say each of these “should not be done” by Congress or the Trump administration.

Some Bipartisan Agreement on Health Care Priorities, but Views on ACA Are Highly Partisan

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., President Trump’s choice for head of the Department of Health and Human Services has long touted the need for a complete overhaul of U.S. food policy including cracking down on ultra-processed foods and food dyes. This focus on limiting chemicals in the public’s food supply is echoed in the public’s list of top health care priorities, with majorities across partisans saying it should be a top priority for the new Trump administration and Congress. More than half of Republicans (61%), independents (56%), and Democrats (55%) say setting stricter limits on chemicals in the food supply should be a “top priority” for Congress or the Trump administration.

Majorities of Democrats and independents also say oversight – both boosting price transparency rules to ensure health care prices are available to patients and more closely regulating health insurance companies’ approval or denial of care – should be a top priority for lawmakers. This increased oversight on hospital pricing and insurance companies is also seen as a priority among large shares Republicans (56% and 45%, respectively). Partisans also hold similar views on whether expanding the number of drugs subject to Medicare price negotiation should be a priority, with about half of Republicans (48%) saying this should be a “top priority,” as do nearly two-thirds of Democrats (65%).

There is also bipartisan agreement on what shouldn’t be a top health care priority for lawmakers. Few Democrats, independents, or Republicans think the incoming administration should prioritize changing recommendations for fluoride in local water supplies, reducing federal funding to schools that require vaccinations, limiting abortion access, or reducing federal funding for Medicaid.

On the other hand, views on the future of the 2010 Affordable Care Act continue to be partisan. Repealing the ACA continues to rank as a priority for Republicans (40% say it is a “top priority” in the most recent tracking poll), but it has dropped as priority among the total public (down 10 percentage points), and among Republicans specifically (down 23 percentage points), since the start of the first Trump administration. Democrats, on the other side of the political aisle, are more likely to prioritize extending the Biden-era enhanced ACA marketplace subsidies. Half of Democrats say this should be a “top priority” compared to just about one in six Republicans.

Many Americans Expect Their Health Costs To Continue Increasing

Throughout the 2024 presidential campaign, voters consistently said they were most interested in electing a candidate who could reduce their health care costs. President Trump largely capitalized on voters’ economic concerns and his own record to convince voters that he was the candidate most adept at taking on the high cost of health care. Yet, few Americans now expect health care costs for them and their family members to become more affordable over the next few years. In fact, more than half (57%) of the public – including 54% of Trump voters – say they expect the cost of health care to become “less affordable.” Majorities of Democrats (60%), independents (59%), as well as half of Republicans (51%) all expect health care costs for them and their family members to become less affordable in the coming years.

Public Largely Holds Favorable Views of Government Health Programs

With the Trump administration’s focus on tax cuts and border security, House Republicans have been coming up with plans to pay for these which may include reducing spending on government health programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and the Affordable Care Act. Yet, changes to these programs may run up against public sentiment according to the latest KFF Tracking Poll.

KFF has asked the public about their attitudes about both Medicaid and Medicare for more than two decades, and these two programs continue to be overwhelmingly popular among the public. In the most recent poll, about eight in ten (82%) Americans hold favorable views of Medicare and more than three-fourths (77%) hold favorable views of Medicaid.

Medicare, the federal government health insurance program for adults 65 and older and some younger adults with disabilities, has maintained favorability among eight in ten adults for nearly a decade. In the January KFF Health Tracking Poll, the share who say they view the program favorably includes three-fourths of Republicans (75%) and more than eight in ten independents (84%), and Democrats (90%). This also includes 94% of the individuals who are currently enrolled in the Medicare program.

Similarly, Medicaid, the federal-state government health insurance program for certain low-income individuals and long-term care program, is also very popular with three-fourths of adults (77%) holding favorable views, including six in ten Republicans (63%), and at least eight in ten independents (81%) and Democrats (87%). Medicaid is also popular among those enrolled in the program with 84% saying they view the program favorably.

Notably, both programs are also viewed favorably by a majority of voters who say they voted for President Trump in the 2024 election.

While lawmakers are discussing changes to these programs including significant cuts to Medicaid, about half of the public actually think the federal government isn’t spending enough on either of these programs. About half of the public (51%) say the federal government spends “not enough” on Medicare, while one-third say the government spends “about the right amount” and about one in seven (15%) say the government spends “too much.” A majority of Democrats (60%) and pluralities of independents (49%) and Republicans (43%) say the federal government doesn’t spend enough on Medicare.

Nearly half (46%) say the federal government doesn’t spend enough on the Medicaid program, with another third saying it spends “about the right amount” and around one in five (19%) saying it spends “too much.” While most Democrats (62%) say the federal government doesn’t spend enough, Republicans are a bit more divided with about similar shares of Republicans saying the government spends “too much” (34%), “not enough” (32%), or “about the right amount” (33%) on Medicaid.

The Affordable Care Act, the Obama-administration health insurance program that was a frequent target of the first Trump administration, also continues to be popular – although to a somewhat lesser degree than Medicaid or Medicare. Nearly two-thirds of the public (64%) view the 2010 ACA favorably while less than four in ten (36%) say they hold an unfavorable view of the law. The share of the public who views the law unfavorably continues to be largely made up of Republicans, with about three-fourths (72%) saying they have an unfavorable view. ACA favorability increased substantially during the 2017 repeal efforts, and has maintained majority support throughout the past four years of the Biden administration.

With possible changes to all three government health programs, the public is worried that people covered by each of these programs in the future will not be able to get the same level of benefits that are available today. About eight in ten (81%) say they are either “very worried” or “somewhat worried” that Medicare enrollees will not get the same level of benefits in the future. This includes more than eight in ten (82%) individuals who are currently covered by the program as well as about nine in ten adults (88%) who will be eligible for the program in the coming years, those between the ages of 50 and 64.

In addition, seven in ten are worried about the level of benefits that will be available to people covered by Medicaid (72%) and people who buy their own coverage through the ACA marketplaces (70%). Both Medicaid and the ACA have repeatedly been discussed as possible focuses of the incoming Trump administration and Congressional Republicans.

Many Think Federal Government Isn’t Spending Enough on Public Health

As the Trump administration is balancing spending priorities, the public thinks the government isn’t spending enough on many facets of public health, including both the priorities of RFK Jr, Trump’s pick to lead HHS, and the priorities of Congressional Republicans.

Most of the public says the government is spending “not enough” on the prevention of chronic diseases (60%) or prevention of infectious diseases and preparing for future pandemics (54%). More than four in ten said the government was spending “not enough” (45%) on biomedical research, while 38% said it was spending “about the right amount.” Smaller shares say the federal government is spending “too much” on each of the key health priorities asked about.

Public Thinks Government Efficiency Could Decrease Federal Spending, but Worries Efforts May Reduce Benefits

One of the Trump administration’s promises has been to cut excessive government spending, including reducing fraud and waste across various sectors of the government. As the newly-formed “Department of Government Efficiency” or DOGE begins work, the public is concerned about the impact that government efficiency efforts will have on people who get their health insurance through Medicare or Medicaid.

Overall, the public thinks that reducing fraud and waste in government health programs could lead to reductions in overall federal spending – which is the goal of the government efficiency program, but many also think it will result in a reduction of benefits. Four in ten say reducing fraud and waste in government health programs could lead to “major reductions” in federal spending with an additional third (32%) saying it could lead to “minor reductions.” This includes majorities across partisans (80% of Republicans, 68% of Democrats, and 72% of independents) who say reducing fraud and wasted could reduce overall federal spending.

Yet, more than half (55%) of the public also say reducing fraud and waste could lead to reductions in the benefits people receive from the programs. More than a quarter (28%) of the public say that reducing fraud and waste will lead to “major reductions,” with an additional quarter who say it will lead to “minor reductions” in benefits. Once again, more than half across partisans (60% of Republicans, 55% of Democrats, and 51% of independents) say that reducing fraud and waste will lead to reduced benefits.

The public is largely divided on whether the incoming Trump administration’s proposed efforts to improve government efficiency will have a negative or positive impact on people who get health coverage through Medicare or Medicaid. Similar shares say the impact will be “mostly negative” (43%) and “mostly positive” (41%), while 15% say there won’t be any impact. Views of the impact are highly partisan, with large majorities of Democrats (78%) saying there will be a mostly negative impact, and most Republicans (80%) say there will be a mostly positive impact. Independents are more divided, but a larger share say there will be a mostly negative impact (43%).