There’s been a lot of buzz in the media in early 2025 about the likelihood of Medicaid cuts to significantly reduce federal spending on the program. With almost 72 million people covered by Medicaid, there is widespread concern about what sort of cuts are likely.

This article examines what could be cut – and who the cuts would likely affect.

Why we think Medicaid cuts are likely

Medicaid cuts are making the news due to a Congressional budget proposal that calls for reducing federal spending by hundreds of billions of dollars to pay for various tax cuts. Both chambers of Congress have agreed on a framework for the budget. They ultimately have to agree on details of a budget change, and we don’t yet know how that will unfold.

But the budget framework passed by both the House and Senate directs the Committee on Energy and Commerce, which is the House committee with jurisdiction over Medicaid, Medicare, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, to reduce the federal deficit by $880 billion over 10 years. According to the Congressional Budget Office, cuts of that magnitude would have to primarily target Medicaid.

What Medicaid cuts are being considered?

So what Medicaid cuts could Congress make, and how would they affect enrollees? While we don’t yet know what will be in the final budget bill, we do have information from the House Ways & Means (W&M) and Budget Committees, outlining various cuts, along with potential savings.

Here’s a look at five likely focus areas for Medicaid cuts:

1. Medicaid work requirements

Potential funding cut: About $100 billion over a decade

Medicaid work requirements are not a new idea. Several states received federal approval for work requirements under the first Trump administration, although most were never implemented. Georgia, which has had a work requirement in place since mid-2023 for certain adults, is currently the only state that requires some enrollees to be working to qualify for Medicaid.

If a federal Medicaid work requirement were implemented, the impact would depend on several factors, including:

- How widely the work requirement would apply (for example, only to the Medicaid expansion population, or to all adults under a certain age).

- What populations would be exempt.

- The degree to which compliance could be determined automatically versus requiring enrollees to report their work hours.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation estimates applying a federal work requirement just to the Medicaid expansion population could result in 4.6 to 5.2 million people losing Medicaid eligibility.

2. Remove the floor on the federal Medicaid matching rate

Potential funding cut: $387 billion over a decade

May impact: 10 states and Washington, DC

Medicaid is jointly funded by the federal and state governments. In states with lower per-capita incomes, the federal government pays a larger share of total Medicaid costs. But there’s a minimum 50% matching rate, so the federal government always pays at least 50% of total Medicaid costs.

The W&M Committee projects that federal Medicaid funding could be reduced by $387 billion over the coming decade if the 50% minimum was eliminated, allowing higher-per capita income states to receive less federal funding for Medicaid. (If the 50% floor is removed and some states end up with lower federal matching rates as a result, the federal government would spend less to fund those states’ Medicaid programs, resulting in savings for the federal government.)

This change would impact 10 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Washington, and Wyoming. Their total Medicaid enrollment accounts for about 26.4 million of the 71.8 million people enrolled in Medicaid nationwide.

If the federal matching rate were reduced under this proposal, states would have to determine how to account for the funding shortfall, potentially leading to benefit cuts or changes in eligibility rules.

In Washington, DC, federal Medicaid funding is statutorily set at 70%. The W&M list and the Budget Committee call for this to be changed so that the funding percentage would be set the same way it is in the rest of the country, which would reduce it to 50%. If the 50% minimum were to be eliminated as well, the District of Columbia could potentially be subject to additional federal Medicaid funding cuts.

3. Reduce the federal matching rate for Medicaid expansion

Potential funding cut: $561 billion over a decade

Population potentially affected: 20 million people who have gained coverage due to Medicaid expansion

Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the federal government pays 90% of the cost of covering the Medicaid expansion population. This is much larger than the federal government’s share of the cost of covering the rest of the Medicaid population, which ranges from 50% to nearly 77%, depending on the state.

The House Committees want to reduce the federal funding percentage for the Medicaid expansion population so that it matches the funding percentage that applies to the rest of each state’s Medicaid population. This change could save the federal government up to $561 billion over the coming decade.

In nine states, this would result in an automatic termination of Medicaid expansion, and in three others, it would result in an automatic review process that would likely lead to coverage losses. The rest of the states would have to consider whether Medicaid expansion would continue to be financially feasible with the reduced federal funding.

Depending on how the rest of the states would handle the reduction in funding, up to 20 million people could lose Medicaid due to a reduction in federal funding for Medicaid expansion.

4. Implement per-enrollee caps on federal funding

Potential funding cut: Up to $900 billion over a decade

Population potentially affected: 72 million Medicaid enrollees

The W&M Committee estimates that a per-capita cap on federal Medicaid funding could save the federal government up to $900 billion over the next ten years.

Under current rules, federal Medicaid funding is based on the federal government matching the amount that states spend at least dollar-for-dollar, and in some states, up to $3 in federal funding is provided for every dollar the state spends. This is an open-ended match, with no limit on how much federal funding a state can receive.

If Congress switched federal Medicaid funding to a per-capita (per-enrollee) cap, the federal government would give a certain amount of money to each state based on a preset formula, independent of states’ actual costs.

A recent Urban Institute analysis found that states would see significant reductions in federal Medicaid funding under per-capita caps and “would have to consider a range of policy options, including increasing taxes, shifting state spending away from education and other priorities, cutting Medicaid provider payment rates, and reducing benefits for Medicaid beneficiaries.” The analysis also clarifies that “if states cannot find additional revenues or sufficient savings… inevitably, there would be enrollment cuts.”

If a per-capita cap were to be implemented nationwide, it could potentially affect eligibility and benefits for all 72 million Medicaid enrollees. The specifics would vary from one state to another, depending on the approach each state takes.

5. Rescind Biden administration rules

Projected funding cut: $285 billion over a decade

All of the proposals discussed above would require Congressional action. But the W&M Committee also noted that federal Medicaid funding could be reduced by up to $285 billion over the coming decade by rescinding some Biden administration rules. This could be done by federal agencies and would not require Congressional action.

The first Biden administration rule is one that expands access to Medicaid Home and Community Based Services (HCBS).

The other Biden administration rule is a two-part rule that makes it easier for people who are eligible for Medicaid to enroll in the program and renew their coverage.

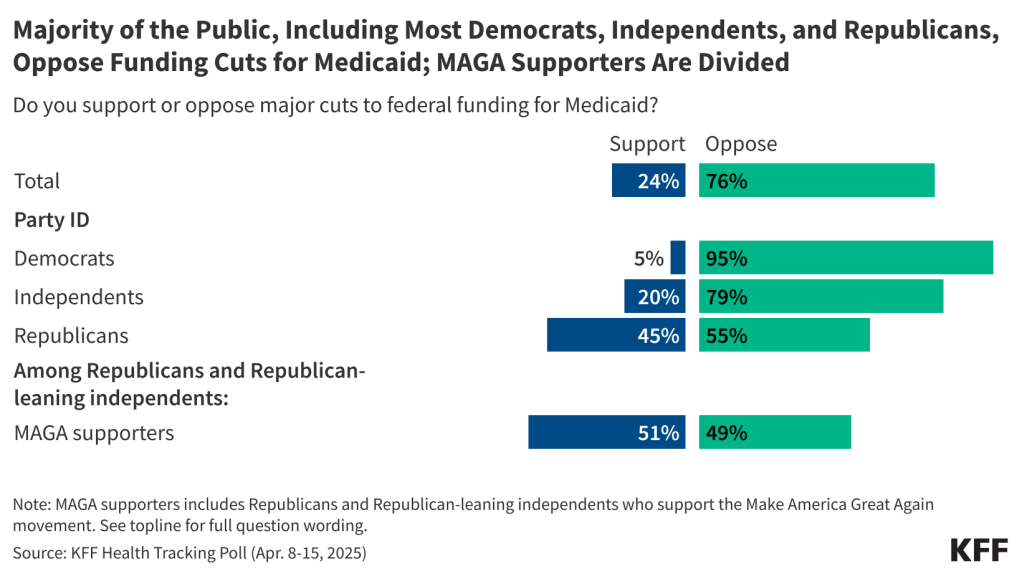

Medicaid cuts would result in reduced benefits and enrollment

According to the Economic Policy Institute, extending tax cuts would primarily benefit those with the highest incomes, while Medicaid cuts would result in people with the lowest incomes losing benefits and coverage. And the impact of Medicaid cuts would apply disproportionately to people of color and children.

Amid pushback on the idea of Medicaid cuts, Republican lawmakers have noted that their intent is to improve efficiency and administration in the Medicaid program, but not to cut benefits or eligibility. However, the scale of federal funding cuts called for in the Congressional budget resolution would require changes like the ones detailed above, which experts agree would result in reduced benefits, fewer enrollees, or both.

Based on historical experience, when people are disenrolled from Medicaid, the majority end up being uninsured for at least some time after losing Medicaid.

So if any Medicaid cuts are implemented, it will be important to devise a strategy that minimizes the number of people who become uninsured.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of HealthInsurance.org, LLC or its affiliates.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written hundreds of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.