National health expenditure reached $4.5 trillion in 2022, accounting for 17% of the gross domestic product (GDP), and is expected to outpace GDP growth through 2032. This growing expenditure is likely to increase costs for families, employers, states, and the federal government. As policymakers explore various strategies to enhance health care affordability, they are paying close attention to the effects of market consolidation in health care and its potential impact on costs and quality of care. Hospital consolidation is a primary focus because nearly one third of all health care spending is directed towards hospital services. While consolidation could enable providers to function more efficiently and assist struggling providers in underserved areas, it frequently results in diminished competition. A wealth of evidence indicates that consolidation can lead to increased prices, with ambiguous effects on quality.

This analysis investigates the competitiveness of hospital care markets by using RAND Hospital Data, a refined version of cost reports from Medicare-certified hospitals, along with American Hospital Association (AHA) survey data. For conciseness, the terms “independent hospitals” and “health systems” will both be referred to as “health systems.” Competition is quantified in three different ways: the proportion of metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) dominated by a limited number of health systems, the level of market concentration in MSAs using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), and the evolving share of hospitals associated with health systems. This analysis concentrates on general short-term or general medical and surgical hospitals based on 2022 data, excluding federal hospitals (see Methods for more information).

Key Takeaways

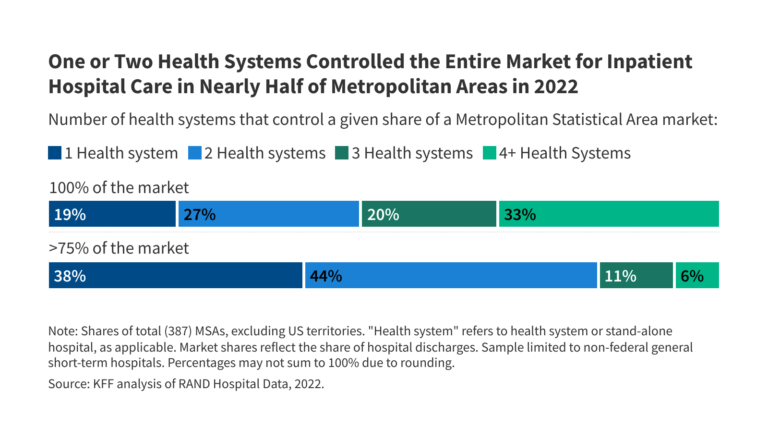

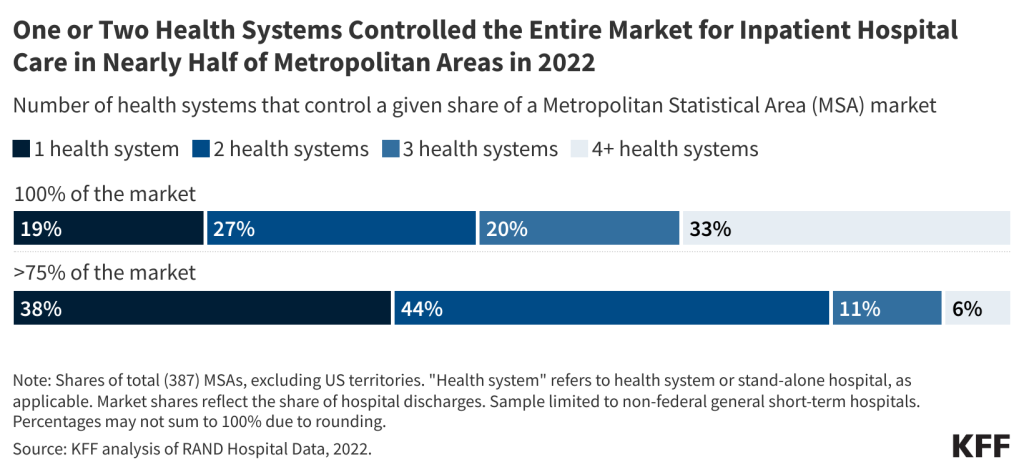

- In 2022, one or two health systems monopolized the entire market for inpatient hospital care in nearly half (47%) of metropolitan areas.

- In over 82% of metropolitan areas, one or two health systems commanded more than 75 percent of the market.

- Almost all (97%) metropolitan areas exhibited highly concentrated inpatient hospital care markets when applying HHI thresholds from antitrust guidelines.

One or Two Health Systems Dominated the Entire Market for Inpatient Hospital Care in Nearly Half (47%) of Metropolitan Areas in 2022

A single health system controlled nearly one in five (19%) metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), while over one in four (27%) markets were governed by two systems in 2022 (see Figure 1). In more than four out of five metropolitan areas (82%), one or two health systems ruled over more than 75 percent of the market. All these markets classified as highly concentrated according to current antitrust guideline definitions (outlined below). One health system held at least half the market share in three out of four MSAs (75%) and at least a quarter of the market in almost every MSA (98%).

The number of health systems within an MSA generally increases in line with the region’s population. For instance, in 79% of MSAs with populations under 200,000, one or two health systems controlled the market for inpatient hospital care in 2022, as seen in locations such as Muncie, IN; Napa, CA; and Amherst Town-Northampton, MA (Figure 2). MSAs with one or two health systems represent nearly half (47%) of all MSAs but only 12% of the U.S. metropolitan population.

On the other hand, almost all (53 out of 54) MSAs with populations of one million or more had at least four health systems, as is the case for Detroit, Miami, and Phoenix. These MSAs with four or more health systems make up 35% of all MSAs and 79% of the U.S. population residing in metropolitan areas.

However, in nine of these relatively large MSAs with four or more systems, the two largest health systems had control over at least 75% of the market. Moreover, in 37 of these markets, they accounted for at least 50%. For instance, in the MSA encompassing Austin, TX, with a population of 2.4 million, two systems (HCA Healthcare and Ascension Health) dominated 85% of the inpatient hospital care market, even though Austin hosts more than four health systems. The metropolitan area covering Portland, OR, with a population of 2.5 million and also more than four health systems, showcases a slightly less concentrated market compared to Austin’s; however, the two largest systems (Legacy Health and Providence) still collectively hold 56% of the market. (Refer to Methods for a discussion regarding MSAs as hospital market geographies).

Nearly all (97%) metropolitan areas had highly concentrated markets for inpatient hospital care in 2022 based on current antitrust guidelines

Another approach to evaluating market competitiveness involves analyzing concentration through the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), which gauges the number of competitors in a market and their market shares. The scale ranges from 0 (indicating perfect competition) to 10,000 (indicating a monopoly). According to current merger guidelines from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Department of Justice (DOJ), markets are categorized as: not concentrated (HHI < 1,000), moderately concentrated (1,000 – 1,800), and highly concentrated (HHI > 1,800). This analysis calculates HHIs for MSAs and classifies these regions accordingly, although alternative market boundary definitions can yield different competition levels (see Methods).

In 2022, nearly all (97%) MSAs showed high market concentration for inpatient hospital care, based on HHI thresholds from current merger guidelines (Figure 3). These guidelines reflect 2023 updates that lowered the HHI thresholds for moderately and highly concentrated markets. Under previous guidelines, a large proportion—though marginally smaller (93%)—of MSAs were classified as highly concentrated markets, corroborating an estimation from a previous study (90%) using 2016 data.

Similar to the findings regarding the number of health systems in MSAs, more populated metropolitan areas generally tended to be less concentrated and more competitive than those with smaller populations, though this wasn’t universally true. All 13 MSAs identified as either not concentrated or moderately concentrated had populations exceeding one million, including places like Cincinnati, Oklahoma City, and Miami. Nevertheless, 41 MSAs with populations greater than one million—including Houston, Denver, and Atlanta—exhibited highly concentrated hospital markets. Overall, 70% of individuals residing in metropolitan areas lived in highly concentrated hospital markets.

The proportion of hospitals affiliated with health systems rose from 56% in 2010 to 67% in 2022, with growth observed in both rural and nonrural areas

As of 2022, approximately two-thirds of hospitals (67%) are affiliated with larger systems, a rise from 56% in 2010 (Figure 4). A lower percentage of rural hospitals than nonrural ones were part of a health system in 2022 (52% vs. 83%), though both rural and nonrural areas have seen an upward trend: from 43% in 2010 to 52% in 2022 among rural hospitals, and from 69% in 2010 to 83% in 2022 among nonrural hospitals.

As of 2022, the majority of system-affiliated hospitals (53%) belonged to systems with at least 15 hospitals, while 22% were part of systems with 50 or more hospitals. Systems with at least 100 hospitals accounted for 13% of system-affiliated hospitals.

Hospital consolidations into larger systems do not always result in diminished local market competition, especially if an independent hospital is absorbed by a larger system that lacks existing facilities in that locality. Nonetheless, mergers across hospitals that serve distinct geographic markets for patient care—termed “cross-market” mergers—may still lead to escalated prices in certain instances.

This work received partial support from Arnold Ventures. KFF retains complete editorial independence over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism efforts.

Methods

|

| Market share and HHI analyses (e.g., Figures 1 through 3) were based on RAND Hospital Data, which represents a cleaned and processed dataset from annual cost reports submitted by Medicare-certified hospitals to the federal government. While this data applies only to Medicare-certified hospitals, it covered the vast majority (97%) of non-federal general medical and surgical hospitals included in US metropolitan areas for our AHA Annual Survey Database analysis (detailed below). Cost reports were assigned to specific years based on the reporting period’s conclusion and adjusted to align with a 365-day period, as needed.

Market share and HHI calculations were confined to non-federal, general short-term hospitals. Market shares were determined by the proportion of inpatient discharges in an MSA attributed to a particular health system or independent hospital. One percent of hospitals meeting our sample restrictions had missing inpatient discharge data and were omitted. Hospitals were organized into health systems based on the 2022 AHRQ Compendium of US Health Systems. MSAs reflect the 2023 geographic definitions established by the Census Bureau, derived from data from the 2020 decennial census. HHIs were calculated by squaring the market shares of all health systems in a given MSA (e.g., if an MSA were evenly divided between two systems, the HHI would be 502 + 502 = 5,000). We retrieved 2022 MSA population estimates from the Census Bureau.

MSAs were utilized as proxies for hospital markets, a common method followed by other studies analyzing hospital market competition nationwide. Alternate market definitions may result in different competition assessments. For example, some recent reports have also focused on MSAs but emphasized the locations where residents received care, which can include hospitals outside the MSA. Other market definitions might utilize Hospital Referral Regions (HRRs) or USDA Commuting Zones. However, more precise market definitions, such as those used in antitrust cases, were not practical. This study did not exclude MSAs with populations of three million or more, as some analyses have done, because this investigation aimed to describe competition across all metropolitan areas.

The share of hospitals affiliated with systems is analyzed based on the AHA Annual Survey Database, which includes a system affiliation measure. This analysis was restricted to nonfederal, general medical and surgical hospitals. Hospitals were classified as rural if located in ZIP codes qualifying for Rural Health Grants via the Federal Office of Rural Health Programs.

|