rewrite this content and keep HTML tags

Key Takeaways

- Amid sweeping overhauls of federal health agencies in the first 100 days of President Trump’s second term, majorities of the public oppose major cuts to staff and spending at these agencies (61%) and say recent actions by the administration and Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) have gone too far (54%). In addition, six in ten (59%) say the administration is “recklessly making broad cuts to programs and staff, including some that are necessary for agencies to function,” while a smaller share (41%) say “the administration is carefully making cuts to programs and staff to reduce fraud and waste, and to improve government efficiency.”

- Views of cuts to staff and spending are largely partisan with most Democrats and independents opposing the cuts and thinking they go “too far,” while a majority of Republicans support the cuts and six in ten (63%) say the extent has been “about right.” In addition, nine in ten Democrats and two-thirds of independents categorize the cuts as reckless while eight in ten Republicans think the administration is carefully making the cuts. Across the board, the strongest proponents of these cuts are MAGA supporters, a group that constitutes about three-quarters of all Republicans and Republican-leaning independents. Large majorities of MAGA supporters say they support the cuts and a quarter say the cuts haven’t gone far enough. Much smaller shares of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents whose views don’t align with the MAGA movement approve of the current actions by the Trump administration.

- Most of the public also see the negative consequences from these cuts, with majorities saying cuts to staff and spending at federal health agencies will have a negative impact on health care for veterans, research to find cures and treatments for cancer and other diseases, efforts to combat the spread of infectious diseases, and food safety. Once again, views are partisan with most Democrats and independents saying the cuts will have a negative impact in these areas while Republicans are more likely to say the cuts won’t have an impact.

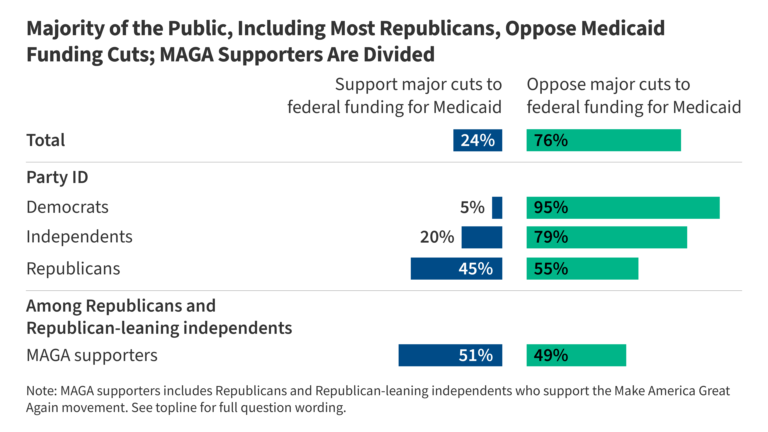

- There is partisan agreement when it comes to funding cuts to Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security with more than nine in ten Democrats, eight in ten independents, and more than half of Republicans opposing federal funding cuts to each of the three government programs. In addition, majorities across partisanship oppose funding cuts to states for mental health and addiction prevention services and for tracking infectious disease outbreaks. Another seven in ten oppose cuts to federal funding for research at universities and medical centers, including nine in ten (92%) Democrats, seven in ten (69%) independents, and almost half (44%) of Republicans. Overall, two-thirds (65%) oppose cutting funding to help people who purchase health coverage through the ACA to pay their premiums (65%), but about six in ten Republicans support major cuts in this area.

- Most of the public agree with the Trump administration that fraud, waste, and abuse are a problem in health care in the U.S., yet partisans disagree on whether the cuts will make any difference and on who is responsible for it. Roughly four in ten (43%) of the public say cuts to staff and spending at government health agencies will negatively impact reducing fraud, waste, and abuse in health care, which is similar to the share (38%) who say there will be a positive impact. Additionally, while majorities (57%) think fraud, waste and abuse are a “major problem” in private health insurance plans, fewer – about half – think fraud is a problem in Medicaid (52%), Social Security (51%), and Medicare (50%). Half of Democrats identify private health insurance companies as the group most responsible for fraud, waste, and abuse in government health programs while four in ten Republicans place the blame on government employees running the programs.

Most Oppose Trump Administration Cuts to Federal Health Agencies

The first few months of President Donald Trump’s second term have been punctuated by a wave of cuts to the federal workforce and government funded programs, especially in health care agencies. At least 20,000 jobs have been lost from the Department of Health and Human Services and its sub-agencies since Robert F. Kennedy Jr. assumed his job as secretary of the agency.

Most of the public (61%) oppose major cuts to staff and spending at federal health agencies, while two in five (38%) support such cuts. Views on the cuts to staff and spending are expectedly partisan, with the majority of Republicans supporting major cuts (72% support, 27% oppose), while nine in ten Democrats oppose the cuts (89% oppose, 10% support). Two-thirds of independents oppose the cuts (67%) while a third are in support (32%).

Support for major changes at federal government health agencies is driven by the most enthusiastic segment of President Trump’s political base – Republicans and Republican-leaning independents who identify as supporters of the Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement. This group, which makes up 75% of Republicans and leaners (31% of total U.S. adults) are demographically similar to other Republicans and Republican-leaning independents when it comes to race/ethnicity, gender, and income, but tend to be older. Roughly eight in ten MAGA-aligned Republicans say they generally support major cuts to staff and spending at federal health agencies, while non-MAGA Republicans are more divided (48% support and 52% oppose).

Perhaps a reflection of the entrenched partisan views, hearing arguments for and against major cuts to staff and spending for federal government health agencies causes few people to change their views. When those who support cuts to the agencies hear that the cuts would negatively impact these agencies’ abilities to serve the public, about a quarter change their view, dropping overall support for the cuts to agencies nine percentage points, from 38% to 27%.

When opponents of the major cuts to federal government health agencies hear that it would help save money and reduce the size and scope of the federal government, about one in ten change their view, increasing overall support eight percentage points to about half (46%) of the public, while 53% remain opposed to the change. On many health issues, polls find that arguments can lead to large shifts in opinion, but that doesn’t seem to be the case here, with majorities continuing to oppose cuts in the face of arguments for them.

Most of the public (54%) say cuts to staff and spending at federal government health agencies by the Trump administration and Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) go “too far” while three in ten (31%) think the cuts are “about right” and 14% say the cuts haven’t gone far enough. Republicans are largely in favor of the level of cuts at the federal government health agencies with six in ten (63%) saying the cuts have been “about right.” This is in stark comparison to the nine in ten Democrats (90%) and six in ten independents (57%) who say the cuts to health agencies have gone “too far.” MAGA Republicans are also much more likely than non-MAGA Republicans to say the cuts to staff and spending at federal government health agencies so far are “about right”, (64% vs. 46%). In fact, one-third (33%) of non-MAGA Republicans think the cuts have gone “too far.”

In addition to believing the cuts have gone “too far,” the public expresses generally negative views about the manner in which the administration has approached these cuts. Asked which comes closer to their view, six in ten (59%) say “the administration is recklessly making broad cuts to programs and staff, including some that are necessary for agencies to function,” while a smaller share (41%) say “the administration is carefully making cuts to programs and staff to reduce fraud and waste, and to improve government efficiency.” Overall sentiment on this question is largely driven by partisanship. Large majorities of both Democrats (92%) and independents (65%) say the cuts have been reckless, while this view is shared by only one in five Republicans (18%). On the other hand, eight in ten (82%) Republicans think the administration is carefully making the cuts. MAGA supporters are much more likely to say that the administration is “carefully making cuts to programs and staff to reduce fraud and waste, and to improve government efficiency” compared to non-MAGA Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (87% vs. 57%). Notably, four in ten non-MAGA Republicans (42%) say the cuts have been reckless.

There is Large Opposition to Funding and Staff Cuts at Government Health Agencies

With tepid support for cuts generally, very few also support major cuts to federal funding for specific programs such as Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security. The House budget resolution is targeting federal cuts to Medicaid for up to $880 billion or more over the next 10 years, representing 29% of state-financed Medicaid spending per resident. Trump has promised not to cut Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid benefits.

At least three-quarters of the public oppose major cuts to funding for Social Security (84%), for Medicare (79%), and for Medicaid (76%). Beyond these major programs, large shares of the public also oppose cuts in other areas of public health, research, and disease prevention. At least two-thirds oppose cutting funding to states for mental health and addiction prevention services (74%), for tracking infectious disease outbreaks (71%), for research at universities and medical centers (69%), for HIV prevention programs (65%), and to help people who purchase health coverage through the ACA to pay their premiums (65%). About one-third or fewer support major cuts to federal funding in each of these areas.

Views on cuts to federal health spending are predictably partisan, with about nine in ten Democrats and at least two-thirds of independents opposed to funding cuts in each area included on the survey. On the other hand, about six in ten Republicans support major cuts to federal funding to help people who purchased coverage through the ACA to pay their premiums (61%) and for HIV prevention programs (61%), while about half of Republicans support cutting funding for research at universities and medical centers (56%) and for tracking infectious disease outbreaks (49%).

But majorities of Republicans oppose major cuts to funding for Social Security (73%), Medicare (64%), and Medicaid (55%). Additionally, a majority of Republicans (58%) oppose cuts to funding to states for mental health and addiction prevention services.

Many agencies have already undergone major staffing cuts under the Trump administration, including the Department of Veterans Affairs, or VA, which announced a plan to cut 83,000 jobs in March. Majorities of the public oppose major staffing cuts at government agencies with responsibilities in health. The largest opposition is to staffing cuts at the VA, which three-quarters of the public oppose.

At least six in ten of the public also oppose cuts to staff at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS (67%), the Social Security Administration, or SSA (66%), the Food and Drug Administration, or FDA (63%), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC (63%), HHS Office of Infectious Disease & HIV/AIDS Policy (62%), and the National Institute of Health, or NIH (62%).

At least nine in ten Democrats oppose major staffing cuts at each of the health agencies included in the survey, while majorities of Republicans (between 58% and 77%) approve of such cuts at most agencies. One exception is staffing cuts at the Department of Veterans Affairs, or VA, with Republicans divided on the issue, with half supporting the cuts (46%) and half (54%) opposing.

Republicans and Republican-leaning independents who support the MAGA movement largely support the cuts to federal funding and staff, with a few notable exceptions.

Majorities of MAGA Republicans support major cuts to federal funding for HIV programs (66%), to help pay ACA premiums (64%), and for research at universities and medical centers (62%). About half support major cuts for tracking infectious disease outbreaks (51%), for Medicaid (51%), and to states for mental health and addiction prevention services (46%). Yet, fewer than four in ten MAGA Republicans support cutting funding for Medicare (38%) and just three in ten support cutting funding for Social Security.

When it comes to cutting staff, three-quarters support major cuts to staff at the HHS Office of Infectious Disease & HIV/AIDS policy (78%), CDC (78%), NIH (77%), and the FDA (75%). Another two-thirds support major cuts to staff at SSA (65%) and CMS (65%). Notably, less than half of MAGA-supporting Republicans (47%) support cuts to the VA.

Concerns About Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Health Programs

The Trump administration and DOGE have framed the cuts occurring throughout the federal government as eliminating “fraud, waste, and abuse”, implementing DOGE’s cost efficiency initiative. Large majorities of the public think fraud, waste, and abuse are a major problem facing our country’s health care programs, though most don’t view the problem as being limited to public health insurance programs. About six in ten (57%) think fraud, waste and abuse are a “major problem” in private health insurance plans, while about half say the same about Medicaid (52%), Social Security (51%), and Medicare (50%). Close to a third say fraud, waste, and abuse are a “minor problem” in each of these, while about one in ten say fraud, waste, and abuse are “not a problem”.

Republicans are about three times as likely as Democrats to say fraud, waste, and abuse are a major problem in Social Security (80% vs. 26%), Medicaid (75% vs. 25%) and Medicare (72% vs. 24%). There is a much smaller partisan difference in the share seeing fraud, waste, and abuse as a major problem in private health insurance, with two-thirds of Republicans (66%), six in ten independents (61%), and nearly half of Democrats (45%) sharing this view. MAGA-supporting Republicans are much more likely than non-MAGA Republicans to say fraud, waste, and abuse are major problem in private health insurance plans (69% vs. 58%), Medicaid (80% vs. 57%), Social Security (84% vs. 54%), and Medicare (77% vs. 53%).

Adults in the U.S. are divided when identifying culprits of fraud, waste, and abuse in government health programs. One in three (33%) say that private health insurance companies are most often responsible for fraud, waste, and abuse in government health programs, with a similar share (29%) saying government employees running the programs are most responsible. One in five (20%) think hospitals, doctors, and other health care providers are responsible for most fraud, waste, and abuse in government health programs, while one in six (17%) say the same about people enrolled in the programs.

Less than a quarter across partisans blame people enrolled in the programs or hospitals, doctors, and health care providers for fraud, waste, and abuse in government health programs. Instead, half (49%) of Democrats identify private health insurance companies as the group most responsible for fraud, waste, and abuse while four in ten (42%) Republicans place the blame on government employees running the programs.

The Public Is Concerned How Cuts May Impact Services, but Some Think They Will Reduce Fraud and Waste and Bring Down the Deficit

Majorities of the public believe that cuts to staff and spending at federal health agencies will have negative impacts in a variety of areas. Six in ten say these cuts will have a “mostly negative” impact on health care for veterans (62%) and on research to find cures and treatments for cancer and other diseases (60%). More than half of adults say there will be “mostly negative” impacts on efforts to combat the spread of infectious diseases like measles and bird flu (55%) as well as food safety (53%). Half believe the cuts will have a negative impact on racial disparities in health care. Fewer than one in six expect the cuts to have positive impacts in any of these areas.

While President Trump and Elon Musk have framed many of the recent cuts as necessary to curb fraud and waste and reduce the federal budget deficit, the public is divided in their views of whether these goals are likely to be achieved. About four in ten (38%) say staff and spending cuts at federal health agencies will have a “mostly positive” impact on reducing fraud, waste, and abuse in health care, but a similar share (43%) say these cuts will have a “mostly negative” impact on reducing fraud, waste, and abuse. Similarly, while four in ten say cuts will have a positive impact on reducing the U.S. budget deficit, nearly as many (34%) say they will have a “mostly negative” impact.

Most Democrats say the cuts to staff and spending will negatively impact health care for veterans (91%), food safety (91%), research to find cures and treatments for cancer and other diseases (90%), efforts to combat the spread of infectious diseases like measles and bird flu (88%), and racial disparities in health care (87%).

Republicans are more positive about how the cuts will impact the budget and waste in health care, with at least seven in ten saying the cuts will have a “mostly positive” impact on reducing the U.S. budget deficit (73%) and reducing fraud, waste, and abuse in health care (71%). Most Democrats say the cuts to staff and spending will have a “mostly negative” impact in these areas while independents are divided in how they think the cuts will impact fraud and waste as well as reducing the U.S. budget deficit.

Republicans are also more likely than both independents and Democrats to think that the cuts to staff and spending will not have any impact on the areas that affect public health, like racial disparities in health care (65%), food safety (57%), efforts to combat infectious disease (56%), and research to find cures for treatments for cancer and other diseases (52%). Majorities of independents and Democrats think the cuts will have “mostly negative” impacts in each of these areas.