rewrite this content and keep HTML tags

President Trump has just signed an executive order outlining several proposals related to prescription drug prices, including efforts to “improve upon” the Inflation Reduction Act, a law signed by President Biden in 2022 with several provisions to lower prescription drug costs for people with Medicare and reduce drug spending by the federal government. In the new executive order, the Secretary of HHS is directed to work with Congress to implement a change in the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program to delay negotiation of so-called “small molecule” drugs beyond 7 years after FDA approval under current law. This change would mean that small molecule drugs would be on the market longer before they are eligible to be selected for Medicare drug price negotiation, which could lead to higher Medicare prescription drug spending, higher prices, and potentially higher Medicare Part D premiums.

Under current law, high-spending drugs can be selected for negotiation if they are brand-name drugs or biological products without generic or biosimilar equivalents, and at least 7 years (for small molecule drugs) or 11 years (for biologics) past their FDA approval or licensure date when the list of drugs selected for negotiation is published by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). This translates into 9 years for small molecule drugs or 13 years for biologics following FDA approval when Medicare’s negotiated prices take effect. Consistent with the new Trump administration executive order, some members of Congress have proposed legislation supported by the pharmaceutical industry to exempt small molecule drugs from selection for negotiation for an additional 4 years so that both types of drugs would be on the market for 11 years prior to being eligible for selection and for 13 years prior to Medicare’s negotiated prices taking effect.

Compared to biologics, small molecule drugs, which often take the form of pills or tablets, are typically cheaper and easier to manufacturer, easier for patients to take, and less expensive on average. Consequently, the shorter timeframe for selection of small molecule drugs has been characterized by its critics as a so-called “pill penalty,” with the pharmaceutical industry claiming that making small molecule drugs eligible for negotiation sooner than biologics will discourage investment in these drugs. However, changing the law to further delay the selection of small molecule drugs for Medicare price negotiation would come at a cost to Medicare and beneficiaries by giving drug companies 4 additional years of setting their own prices on these drugs prior to being eligible for negotiation by the federal government, unless combined with other changes to prevent higher spending.

If Medicare was not allowed to negotiate prices for small molecule drugs until 11 years after FDA approval, rather than 7 years, more than half of the Part D drugs that were selected for price negotiation in the first or second rounds – 13 out of 25 – would not have been eligible at the time drugs were selected. During the first round of negotiation (for negotiated prices taking effect in 2026), 5 of the 10 selected Part D drugs would not have been eligible for negotiations, based on the number of years since they were approved by the FDA. For the second round of negotiation (for negotiated prices taking effect in 2027), 8 of the 15 drugs would not have been selected (Figure 1, ‘Selected drugs’ tab and Table 1).

A 4-year delay in selecting small molecule drugs for price negotiation would have exempted several drugs with high total gross Medicare Part D spending in the first and second rounds of negotiation. For example, Eliquis and Jardiance, 2 of the top 3 drugs based on total gross Medicare Part D spending selected in the first round, would have been ineligible that year based on their FDA approval dates. Similarly, 2 of the top 3 drugs selected in the second round, Ozempic/Rybelsus/Wegovy (semaglutide) and Trelegy Ellipta, would have been ineligible for selection based on their approval dates. (Despite having an injectable form like many biologics, Ozempic has a molecular structure that enables it to be regulated and approved under the same pathway as small molecule drugs.)

To illustrate the implications of this potential change, under current law, small molecule drugs qualified for selection in round two of negotiation if they were approved by the FDA at least 7 years before the February 1, 2025 publication date of the list of selected drugs, or February 1, 2018, which translates to 9 years before the round two negotiated prices take effect in 2027. Ozempic was approved on December 15, 2017, which is more than 7 years before February 1, 2025, and was eligible for selection in round two under current law. However, if selection of small molecule drugs had been delayed an additional 4 years, as has been proposed, Ozempic would have been ineligible for selection. By extending the period from 7 years to 11 years after FDA approval before small molecule drugs can be selected for negotiation, Ozempic would not be eligible for negotiation until after December 5, 2028, and would have 13 years following FDA approval before Medicare’s negotiated price took effect.

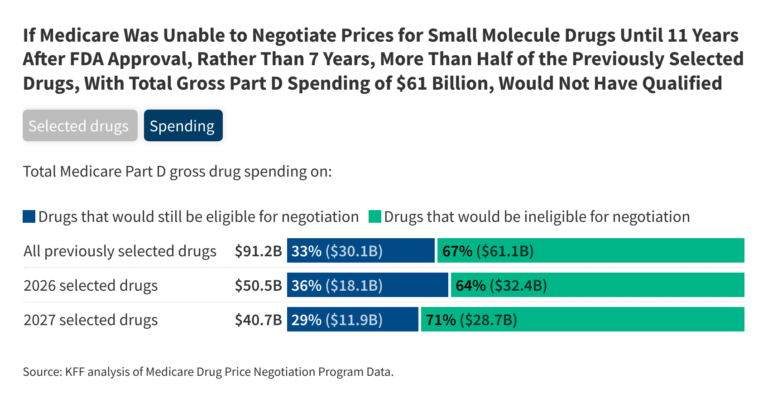

The 13 drugs that would have been ineligible to be selected for negotiations during the first and second rounds under a 4-year delay for small molecule drugs accounted for two-thirds of total gross Medicare Part D spending on the 25 selected drugs, or $61 billion out of $91 billion. The 5 small molecule drugs that would have been ineligible for selection during the first round of negotiations account for $32.4 billion (64%) of the $50.5 billion total gross Part D spending on all 10 selected drugs. This is based on spending between June 2022 and May 2023, the period used to determine gross Part D spending to select drugs for the first round of price negotiation (Figure 1, ‘Spending’ tab).

The 8 drugs that would have been ineligible for selection in the second round account for $28.7 billion (71%) of the $40.7 billion in total gross Part D spending on all 15 selected drugs. This is based on spending between November 2023 and October 2024, the period used to determine gross Part D spending to select drugs for the second round of price negotiations.

If small molecule drugs had been subject to an additional 4-year delay from their FDA approval date prior to being eligible for selection in the first two rounds of Medicare drug price negotiation, Medicare would have had to select several other drugs with lower total gross Part D spending in order to round out the list of selected drugs in each year. This suggests that enacting this change in law could increase Medicare spending relative to current law due to lower savings associated with drug price negotiation, with potentially higher drug prices and premiums for Part D enrollees. While the Trump administration’s executive order suggests that other reforms could be implemented to prevent an increase in overall costs to Medicare and beneficiaries associated with this policy change, it did not specify the details of those changes.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.