rewrite this content and keep HTML tags

The financial health of rural hospitals has been an ongoing concern for some policymakers. More recently, these concerns have been amplified in the context of the concurrent budget resolution that passed the House and Senate in April 2025, with instructions for the House to reduce federal Medicaid spending by up to $880 billion or more over the next decade. The financial challenges of rural and other financially vulnerable hospitals have also been raised in the context of proposals to achieve Medicare savings through site-neutral payment reforms, which would align Medicare payment rates for a given outpatient service across different sites of care. Strains on hospital finances could have implications for both access to care as well as local economies, including in rural areas. Hospitals are the sixth largest employer nationally when comparing industry subsectors. As policymakers consider reductions in Medicaid and Medicare spending, some are considering options to support rural and safety-net hospitals.

In light of these policy discussions, this brief presents ten things to know about rural hospitals, using data from Medicare cost reports, the American Hospital Association (AHA) Survey Database, and other sources (see Methods for more details). Rural hospitals are defined as those in nonmetropolitan areas (and urban hospitals as those in metropolitan areas), in line with a definition used by the Medicare Payment and Advisory Commission (MedPAC), though there are several ways of defining “rural” (see Methods). The federal government also includes nonmetropolitan in its definition of “rural” for certain Medicare rural payment designations. Rural areas are further broken out in this brief into those that are adjacent to metropolitan areas and those that are not. Rural counties that are not adjacent to metropolitan areas are referred to as the “most rural” areas. The analyses focus on community hospitals or non-federal general short-term hospitals that comprise the majority of all hospitals, unless stated otherwise. (See Methods for additional information about the definition of rural and the analytic sample.)

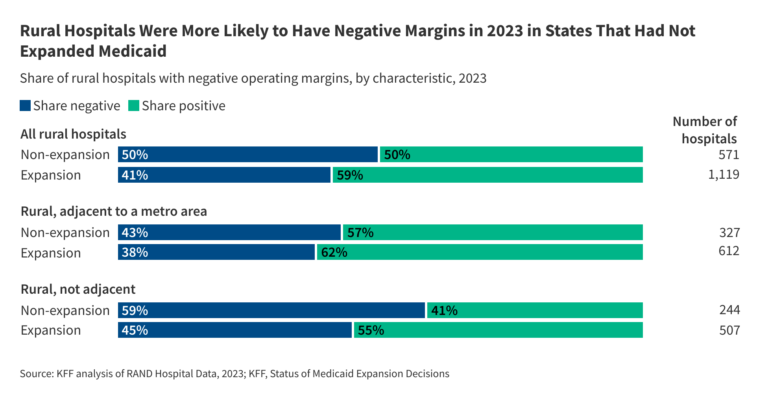

Although rural hospitals more frequently have negative operating margins than urban hospitals, more than half had positive operating margins in 2023 (the most recent year of data available), and nearly one fifth (19%) had margins of at least 10%. Rural hospitals in states that have not adopted the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion were more likely to have negative margins than rural hospitals in expansion states. Among rural hospitals, negative margins were more common among those in the most rural areas, while positive margins were more common among those that had more beds, higher occupancy, were affiliated with a health system, and were not government-owned in 2023.

1. Rural hospitals account for about one third of all community hospitals nationwide and at least a third of all hospitals in most states

About one third (35%) of all community hospitals were in rural areas in 2023 (Figure 1), or 1,796 rural community hospitals. Rural hospitals accounted for only 8% of all discharges nationwide, in part because they tend to be smaller and serve less densely populated areas, contributing to lower volumes than urban hospitals. Forty-six million people lived in rural areas in 2023 as it is defined in this issue brief, most of whom (88%) resided in a county with a hospital.

Rural hospitals operate in nearly every state (48) and account for at least a third of hospitals in most (31) states. In 17 states, rural hospitals accounted for at least half of all hospitals, including states in the Northwest, South, Midwest, and West. Rural hospitals accounted for at least 70% of hospitals in seven states, five of which border each other in the Great Plains: Montana, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Wyoming.

Over two fifths (44%) of rural hospitals were in areas that are not adjacent to metropolitan areas. These hospitals represented 3% of all hospital discharges and operated in 43 states. Fifteen million people lived in rural areas not adjacent to a metro area in 2023 compared to 31 million in rural adjacent areas.

Rural hospitals provide varying types of inpatient and outpatient services. For example, about half of rural hospitals provide obstetrics care (53%), intensive medical and surgical care (50%), and care through a certified trauma center (52%). In 2023, Medicare began to offer a new rural emergency hospital (REH) designation, which provides support to hospitals that operate 24/7 emergency departments but do not provide inpatient care, recognizing that some regions cannot support a broader suite of services.

Rural hospitals tend to have fewer beds, are less likely to be part of a broader health system, are less likely to have for-profit ownership, and are more likely to be government-owned than urban hospitals according to prior KFF analysis, and they are also more likely to have low inpatient occupancy rates. For example, as might be expected, a larger share of rural hospitals (50%) than urban hospitals (14%) have 25 or fewer beds. One third of rural hospitals are owned by a state or local government versus 10% of urban hospitals. About half of all rural hospitals are part of a broader health system, as compared to more than three quarters of all urban hospitals (52% versus 78%). Consolidation may allow providers to operate more efficiently and help struggling providers keep their doors open in underserved areas, but it could also reduce competition—which may lead to higher prices and lower quality—and make hospitals less responsive to their local communities.

2. Medicare covered a larger share of hospital discharges in rural than urban areas in 2023, while private insurance covered a smaller share and Medicaid covered a similar share

Medicare covered a larger share of discharges in rural versus urban areas (53% versus 45%) while Medicaid covered a similar share (19% versus 21%) and private insurance (not including Medicare and Medicaid plans) covered a smaller share (19% versus 24%). Private insurers generally reimburse at higher rates than Medicare and Medicaid.

With Medicaid covering about one fifth of discharges in rural areas, any substantial reduction in Medicaid spending could have a large impact on rural hospital finances, particularly given the lower margins of rural hospitals. In addition to providing primary coverage for many patients, Medicaid also provides secondary coverage for many beneficiaries who are dually enrolled in Medicare.

3. Medicaid covered nearly half of all births in rural areas, the vast majority of which were in hospitals, in 2023

Medicaid covered 1.5 million births in 2023—representing 41% of all U.S. births—and financed nearly half (47%) of births in rural areas (Figure 3). Births are the most common reason for a hospital inpatient stay. The vast majority (96%) of births in rural areas occurred in a hospital in 2023 according to KFF analysis of CDC data.

Decreases in Medicaid spending could accelerate the closure of obstetrics service lines in rural hospitals, in addition to affecting the availability of services at rural hospitals more generally. From 2010 to 2022, 238 rural hospitals closed obstetrics units while only 26 hospitals opened new units. Low Medicaid reimbursement rates and difficulty recruiting and retaining providers were cited as the biggest challenges to providing obstetrics care in rural areas, according to the Government Accountability Office.

4. A larger share of rural than urban hospitals had negative margins in 2023, though more than half of all rural hospitals had positive margins

Despite the government support that most rural hospitals receive, a larger share of rural hospitals had negative operating margins than did urban hospitals in 2023 (44% versus 35%) (Figure 4). A larger share of rural hospitals in areas that were not adjacent to a metropolitan area (i.e., that were in the most rural areas) had negative margins than did rural hospitals in areas adjacent to a metropolitan area (49% versus 40%). Operating margins reflect profit margins earned on patient care and other operating activities, rather than profits earned on other sources, such as investments.

At the same time, more than half (56%) of all rural hospitals had positive operating margins. Further, while about one sixth (15%) of all rural hospitals had margins less than -10%, about one fifth (19%) had margins greater than 10% (data not shown). In other words, financial conditions as measured by operating margins varied substantially across rural hospitals.

Rural hospitals may face financial and operational challenges for a number of reasons. For example, rural hospitals tend to have low patient volumes, stemming from low and declining populations in rural areas and rural patients bypassing local hospitals for treatment at urban facilities. Low patient volumes may lead to higher costs on average—e.g., to the extent that the fixed costs of operating a hospital, such as building upkeep and maintaining a minimum number of administrative and clinical staff, are spread across fewer patients—and limit the ability of rural hospitals to offer specialized services. Many rural areas also have a particularly hard time attracting and retaining health care workers. Both urban and rural hospitals have encountered financial challenges since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, including rising labor and supply costs, although there are signs that hospital finances have been recovering.

5. Among rural hospitals, positive margins were more common among those that had more beds, higher occupancy, were affiliated with a health system, and were not government-owned in 2023.

Large, high occupancy, system-affiliated, and non-government rural hospitals were more likely than other rural hospitals to have positive margins. While 56% of rural hospitals overall had positive margins, the share was larger among hospitals with at least 200 beds (73%), with occupancy rates of at least 75% (70%), and that were affiliated with a broader system (63%). For-profit and nonprofit rural hospitals also more frequently had positive margins (62% and 61% respectively) than rural hospitals overall.

While 44% of rural hospitals overall had negative margins, about half of rural hospitals that had 26-99 beds (52%) and were not affiliated with a broader health system (51%) had negative margins. The likelihood of having negative margins tended to decrease with lower occupancy rates and fewer beds, except that hospitals with 25 or fewer beds were less likely to have negative margins than average. That may reflect the fact that this group mostly includes critical access hospitals, which receive additional government support.

More than half of non-federal, government-owned hospitals (54%)—which make up a third of rural community hospitals—had negative margins. Most government-owned hospitals in rural areas included in this analysis are operated by a county or hospital district.

6. The ACA Medicaid expansion has helped improve hospital finances, and may especially benefit rural hospitals

State Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act has had financial benefits for hospitals according to several studies. The financial impact of Medicaid expansion for at least certain measures may be most evident among rural hospitals, small hospitals, and hospitals that see a higher proportion of low-income patients, based on some of this research.

Half (50%) of rural hospitals in states that had not adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion as of the beginning of 2023 had negative margins in that year, compared to four tenths (41%) of rural hospitals in expansion states. Differences were larger among hospitals in the most rural areas (i.e. in rural areas not adjacent to metropolitan areas). In those regions, about six tenths (59%) of hospitals in non-expansion states had negative margins compared to less than half (45%) of rural hospitals in expansion states. Differences between expansion and non-expansion states could reflect the effects of expansion on hospital finances but could also reflect a variety of unique state circumstances, such as demographics, hospital ownership and cost structure, commercial reimbursement rates, and state and local health and tax policy.

About two thirds (69%) of the rural hospital closures from 2014 to 2024 occurred in states that had not expanded Medicaid at the time according to KFF analysis of data from the UNC Sheps Center. (The Sheps Center has a broader definition of “rural” than used in this brief, such as by including critical access hospitals in metropolitan areas).

7. Hospital closures outpaced openings in rural areas from 2017 to 2024, and many rural hospitals have dropped specific service lines over time.

From 2017 to 2024, 62 rural hospitals closed compared to 10 that opened, a net reduction of 52 hospitals. (Closures refer to hospitals that eliminate inpatient services—aside from those that convert to rural emergency hospitals—or cease operations altogether). Over the longer twenty-year period from 2005 to 2024, 193 rural hospitals closed according to the UNC Sheps Center (which uses a broader definition of “rural” than this brief). The small number of studies that have evaluated the association between consolidation with rural hospital closures and service eliminations have had mixed results.

Aside from closing altogether, rural hospitals have also dropped certain service lines over time. For instance, according to one analysis, the share of rural hospitals offering obstetrics care dropped from 57% in 2010 to 48% in 2022. The share among urban hospitals also dropped over that period (from 70% to 64%) but remained higher than in rural areas in 2022 (64% versus 48%). Government relief funds may have helped some rural hospitals stay open and maintain certain service lines during the COVID-19 pandemic. The new REH hospital designation in 2023 may have helped prevent some rural hospitals from closing according to MedPAC.

Rural hospital closures often raise concerns about access to care and the local economy. When a rural hospital closes, patients may have to travel further to obtain services, which could lead some to forgo care altogether. Closures may be especially problematic for people who have difficulty traveling long distances and for people with time-sensitive conditions, such as heart attacks and childbirth. Research suggests that rural hospital closures lead to increased unemployment (including among non-healthcare industries), lower income levels, and slower economic growth.

While there has been interest among some policymakers in sustaining rural hospitals, doing so may be difficult in certain scenarios—such as in areas with shrinking populations—and could involve tradeoffs. For instance, although rural hospitals can help the local population access care, it is also possible that some of the services they offer can be provided at a lower cost through telehealth or freestanding rural outpatient clinics. Further, while traveling to large regional hospitals may be burdensome for patients in some cases, it is also possible that these hospitals may offer higher quality of care in certain scenarios.

8. Medicare provides additional funding for the large majority (96%) of rural hospitals through special payment designations

Traditional Medicare includes special payment designations targeted towards rural hospitals that can increase payments through the inpatient and outpatient prospective payment systems (IPPS), by reimbursing hospitals based on their costs, or by providing monthly facility payments. The Medicare-dependent designation and an expansion of low-volume hospital adjustments are not permanent but have been renewed over time. Congress passed a continuing resolution in March 2025 that extends these policies through September 30, 2025, and proposed legislation in the Senate would make them permanent.

A hospital may only be designated as one of the following:

- Critical access hospitals (CAHs) are rural hospitals with at most 25 beds that are a minimum distance from other facilities (with some exceptions) and meet other requirements. Medicare pays CAHs 101% of inpatient and outpatient costs (although with sequestration, it reimburses below cost). CAHs receive an estimated $3 to $4 billion in higher payments annually according to a 2022 MedPAC report. CAH is the most common designation, accounting for more than half (59%) of rural hospitals in 2023 (Figure 7).

- Sole community hospitals (SCHs) are hospitals that are the only source of short-term, acute inpatient care in a region. Medicare reimburses some SCHs at higher rates than they would have received under IPPS, including based on historical costs. Since 2006, CMS has also increased OPPS rates for rural SCHs. SCHs receive $0.8 billion in higher payments annually (including low-volume adjustments to SCHs) according to a 2022 MedPAC report.

- Medicare-dependent hospitals (MDHs) are small rural hospitals with high Medicare inpatient shares. Medicare pays MDHs higher rates based on historical costs if greater than IPPS rates. MDHs receive $0.1 billion in higher payments annually according to a 2022 MedPAC report.

- Rural emergency hospitals (REHs) are rural hospitals that operate 24/7 emergency departments but do not provide inpatient care. REHs are reimbursed at 105% of standard OPPS rates and receive monthly facility payments. This designation became available in 2023, recognizing that some areas cannot support a broader suite of services. MedPAC has estimated that REHs cost an additional $30 million in 2023, much lower than original CMS projections for 2023 ($408 million), possibly because fewer hospitals converted to REHs in 2023 than originally anticipated. Nineteen hospitals converted in 2023 (most of which did so in the second half of the year) and an additional 18 converted in 2024 according to the UNC Sheps Center.

There are two additional rural designations that can be applied to a hospital, with additional benefits:

- Low-volume hospitals (LVHs) are hospitals with few discharges that are a minimum distance from other facilities. They receive up to 25% higher payments through the IPPS. LVHs receive $0.4 billion in higher payments annually according to a 2022 MedPAC report.

- Rural referral centers (RRCs) are hospitals that generally either treat patients from across a large region or treat complex cases. Some RRCs are eligible for higher IPPS base payments, among other benefits. Although RRCs are sometimes referred to as a rural payment designation, most (73%) are not in rural areas based on KFF analysis of cost report data. There is no recent estimate for the value of this designation.

While these special payment designations are available for hospitals discharges covered by traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage accounts for a rising share of discharges across the nation, and is growing more rapidly in nonmetropolitan areas, which may pose additional challenges for rural hospitals. Hospitals in rural areas and elsewhere have raised concerns about the growth of Medicare Advantage, pointing to payment delays and denials and lower reimbursement than traditional Medicare. According to the American Hospital Association, Medicare Advantage reimburses rural hospitals at lower rates than traditional Medicare on average. MedPAC has noted that Medicare Advantage plans do not pay REHs monthly facilities payments (in contrast to traditional Medicare), and at least some providers have said they do not receive increased Medicare Advantage payments equivalent to the payment bumps under traditional Medicare rural payment designations. Whether or to what extent rural hospitals experience revenue declines as Medicare Advantage covers a larger share of Medicare patients is unclear.

Other federal programs or policies also provide additional support for rural hospitals. For instance, Medicare adjusts IPPS and OPPS reimbursements based on the wages hospitals pay in a given area (known as the Wage Index), which generally results in lower reimbursement for rural hospitals. However, sole community hospitals and rural referral centers can be more easily reclassified to areas that receive higher reimbursements through the Wage Index. Many state Medicaid programs also have special payment rules for hospitals in rural areas, such as by paying higher rates or based on costs or through supplemental payments. HRSA also administers several programs providing grants, technical support, workforce development, and other assistance to rural hospitals and rural providers more generally. As another example, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) recently concluded its test of the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, which provided rural hospitals with an all-payer global budget and was intended to reduce costs, increase quality, and improve the sustainability of rural hospital finances.

Rural hospitals can also benefit from other programs or payment policies that are available to certain hospitals across the country. This includes higher Medicare reimbursement for Disproportionate Share Hospitals, tax-exempt status for nonprofit hospitals, and participation in the 340B Drug Pricing Program, which requires manufacturers participating in Medicaid to sell outpatient drugs to eligible nonprofit and government providers at a substantial discount, with the intent of supporting entities caring for low-income and other underserved populations. In 2023, critical access and sole community hospitals alone purchased $1.5 billion in 340B drugs.

9. Even with additional funds, about half of sole community, Medicare-dependent, and low-volume hospitals had negative margins in 2023.

About half of sole community hospitals (49%), Medicare-dependent hospitals (52%), and low-volume hospitals (52%) had negative margins in 2023. As discussed below, there have been proposals to increase Medicare reimbursement for these facilities. A smaller share of critical access hospitals (40%) and rural referral centers (37%) reported negative margins in 2023 than hospitals in other designated categories, such as sole community hospitals.

10. Significant reductions in federal spending on health care under consideration would have direct or indirect implications for rural hospitals

The House and Senate passed a concurrent budget resolution in April 2025 with instructions for the House Energy & Commerce Committee to reduce the federal deficit by at least $880 billion over ten years, which the Congressional Budget Office and other analysts have confirmed would require significant cuts to Medicaid. Large reductions in Medicaid would likely have significant implications for hospitals, given that hospital care accounted for about one third of Medicaid spending in 2023. Options under consideration for reducing Medicaid spending include targeting state directed payments to hospitals or restricting states’ ability to fund Medicaid through provider taxes. Because provider taxes disproportionately fund supplemental payments to hospitals, restricting them as a revenue source is likely to result in lower funding for hospitals broadly, including for rural hospitals. Also being considered among other options is reducing the federal share of funding for Medicaid expansion, which has helped improve hospital finances. The hospital industry has been lobbying Congress against proposed cuts, arguing that reductions in Medicaid spending would threaten access to care at hospitals.

Also being discussed are site-neutral payment reforms that would achieve Medicare savings by aligning Medicare payment rates for a given outpatient service across different sites of care. These reforms would reduce payments to hospitals, with the impact varying based on the extent to which a given hospital relies on Medicare outpatient revenues and other factors. MedPAC estimated that one approach applying to on- and off-campus hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) would lead to relatively large decreases in Medicare revenues for smaller and rural hospitals. Other research has found that off-campus HOPDs—the focus of some reforms—account for a smaller share of outpatient revenues in rural versus urban areas.

Some Members of Congress have expressed concern about the impact of site-neutral payment reforms on rural hospitals, though these reforms would likely not apply to many rural hospitals. Site-neutral payment reforms would likely only apply to OPPS reimbursement and would therefore not affect critical access hospitals, which are reimbursed based on costs and account for most rural hospitals (59%; see Figure 7). CMS has excluded sole community hospitals (20% of rural hospitals) from an existing regulation that extends site-neutral payments to clinic visits at off-campus HOPDs, and it is possible that future policies may do the same. Senators Cassidy and Hassan released a framework for site-neutral reforms in November 2024 that would reinvest some of the savings by increasing reimbursement for sole community, Medicare-dependent, and low-volume hospitals, as well as for urban and suburban safety-net hospitals and certain essential services.

Members of Congress have proposed various policies to prop up rural hospitals that could also be used to soften the impact of cuts to federal spending. For example, bills introduced during the last Congress would expand support for rural emergency hospitals, allow for increased reimbursement for Medicare-dependent and sole community hospitals, and eliminate Medicare sequestration for rural hospitals. More recently, Republicans released a menu of options for reducing federal spending in February 2025, which included an offsetting measure that would expand the rural emergency hospital program. Notably, the list of options did not include new sources of funding for urban safety-net hospitals, even though some of the major options for cutting spending would likely have a disproportionate impact on these facilities, including large cuts in Medicaid spending and reductions in Medicare uncompensated care and bad debt payments.

Methods

Urban hospitals are defined as those operating in a metropolitan area, while rural hospitals are defined as those operating in nonmetropolitan areas. A metropolitan area is a county or group of counties that contains at least one urban area with a population of 50,000 or more people. Nonmetropolitan areas include micropolitan areas—which are counties or groups of counties that contain at least one urban area with a population of at least 10,000 but less than 50,000—and noncore areas (areas that are neither metropolitan nor micropolitan). The analysis further breaks down rural areas into those that are adjacent to metropolitan areas (defined as the “most rural” areas in this brief) and those that are not adjacent to metropolitan counties.

There are many different ways of defining rural areas, each of which would capture a different number of hospitals with different characteristics. The Appendix below includes examples of different definitions created by various federal agencies. This analysis defines rural as nonmetropolitan, in line with a definition used by MedPAC, and given the policy relevance of nonmetropolitan areas. The federal government defines “rural” areas as including nonmetro areas and other regions in some instances, such as when administering additional support through Medicare for critical access hospitals, Medicare-dependent hospitals, sole community hospitals, and rural emergency hospitals. Nonetheless, the definition of rural in this brief includes some areas that others would consider to be urban and excludes some areas that others would consider to be rural. For example, the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), which is part of HRSA, uses a broader definition of rural, noting that some large unpopulated regions, such as the Grand Canyon, are in metropolitan counties.

Data for this analysis came from the following sources:

- American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey. Data from an annual survey of all hospitals in the United States and its associated areas. Used for analyses of rural hospital prevalence, hospital discharges, hospital services, payer mix, and system membership.

- RAND Hospital Data. A cleaned and processed version of annual cost reports that Medicare-certified hospitals are required to submit to the federal government. Used for analyses of hospital margins and special Medicare payment designations.

- UNC Sheps Center lists of rural hospital closures and rural emergency hospitals. The former tracks closures among short-term, general acute care, non-federal hospitals in nonmetropolitan and certain other areas and among critical access and rural emergency hospitals. Closure data was was matched to KFF data on Medicaid expansion status and date of expansion to determine the expansion status of a given state when a given rural hospital closure occurred. The latter was used to identify rural emergency hospitals.

- Census Bureau population estimates. This analysis relied on annual population estimates from July 1, 2023 (excluding U.S. territories) from the Census Bureau’s Population Estimates Program.

- MedPAC publications. MedPAC’s March 2025 Report and July 2022 Data Book were used to identify rural hospital openings and closures over time,

This analysis categorized counties and county equivalents as urban (metropolitan) or rural (nonmetropolitan) areas and divided rural areas into those that are or are not adjacent to metropolitan areas based on 2024 Urban Influence Codes from the USDA, as follows:

- Urban

- 1: Large metro (in a metro area with at least 1 million residents)

- 4: Small metro (in a metro area with fewer than 1 million residents)

- Rural, adjacent to a metro area

- 2: Micropolitan, adjacent to a large metro area

- 3: Noncore, adjacent to a large metro area

- 5: Micropolitan, adjacent to a small metro area

- 6: Noncore, adjacent to a small metro area

- Rural, not adjacent to a metro area (“most rural”)

- 7: Micropolitan, not adjacent to a metro area

- 8: Noncore, not adjacent to a metro area and contains a town of at least 5,000 residents

- 9: Noncore, not adjacent to a metro area and does not contain a town of at least 5,000 residents

This analysis uses different groups of hospitals depending on the analysis, as described in the figure notes. Analyses primarily using AHA data focused on community hospitals—which are short-term, non-federal, general and specialty hospitals that are open to the general public—and exclude hospitals in U.S. territories. There were 1,796 community hospitals in rural areas in 2023, representing 92% of all hospitals in rural areas.

Analyses of hospital margins relied primarily on RAND Hospital Data and focused on non-federal general short-term hospitals, excluding those in U.S territories. Those analyses also included other sample restrictions, such as ignoring certain outlier values. Operating margins were approximated as (revenues minus expenses) divided by revenues after removing reported investment income and charitable contributions from revenues. The Methods section of a prior KFF analysis of operating margins includes additional details, such as the limitations of available financial data. Our analyses of margins included 1,690 hospitals in rural areas in 2023. Data for certain characteristics were missing for 1% or less of the sample with margins data.

The analysis of the share of rural hospitals with special payment designations focused on non-federal general short-term and rural emergency hospitals (excluding those in U.S territories), which included 1,787 hospitals in 2023.

Appendix

Examples of Rural Definitions Created by Federal Agencies

Office of Management and Budget (OMB). OMB defines Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs), which include metropolitan and micropolitan areas. A metropolitan area is a county or group of counties that contains at least one urban area (as defined by the Census) with a population of 50,000 or more people. A micropolitan area is a county or group of counties that contains at least one urban area with a population of at least 10,000 but less than 50,000. This brief defines “rural” as nonmetropolitan, as do many researchers and MedPAC, though OMB itself does not do so. The federal government defines “rural” to include nonmetro areas and other regions in some instances, such as when administering additional support through Medicare for critical access hospitals, Medicare-dependent hospitals, sole community hospitals, and rural emergency hospitals.

Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP). FORHP is an office within the Health Resources and Services Agency (HRSA) that distributes grants, technical assistance, and other support to rural areas, including rural hospitals. FORHP defines “rural” as all nonmetropolitan counties, as well as well as some portions of metropolitan counties based on population density, terrain ruggedness, and commuting patterns.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). The USDA Economic Research Service (ERS) maintains multiple definitions of rurality, including Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC), Rural-Urban Commuting Areas (RUCA), and Urban Influence Codes (UIC). Various federal programs use these definitions to administer support for health care and other resources (such as broadband access and housing) in rural areas.

Census Bureau. The Census Bureau classifies urban areas as census blocks (which are smaller geographic areas than counties) with at least 2,000 housing units or where more than 5,000 people reside. Rural areas are regions outside of urban areas. Federal transportation funds are based in part on this classification.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.